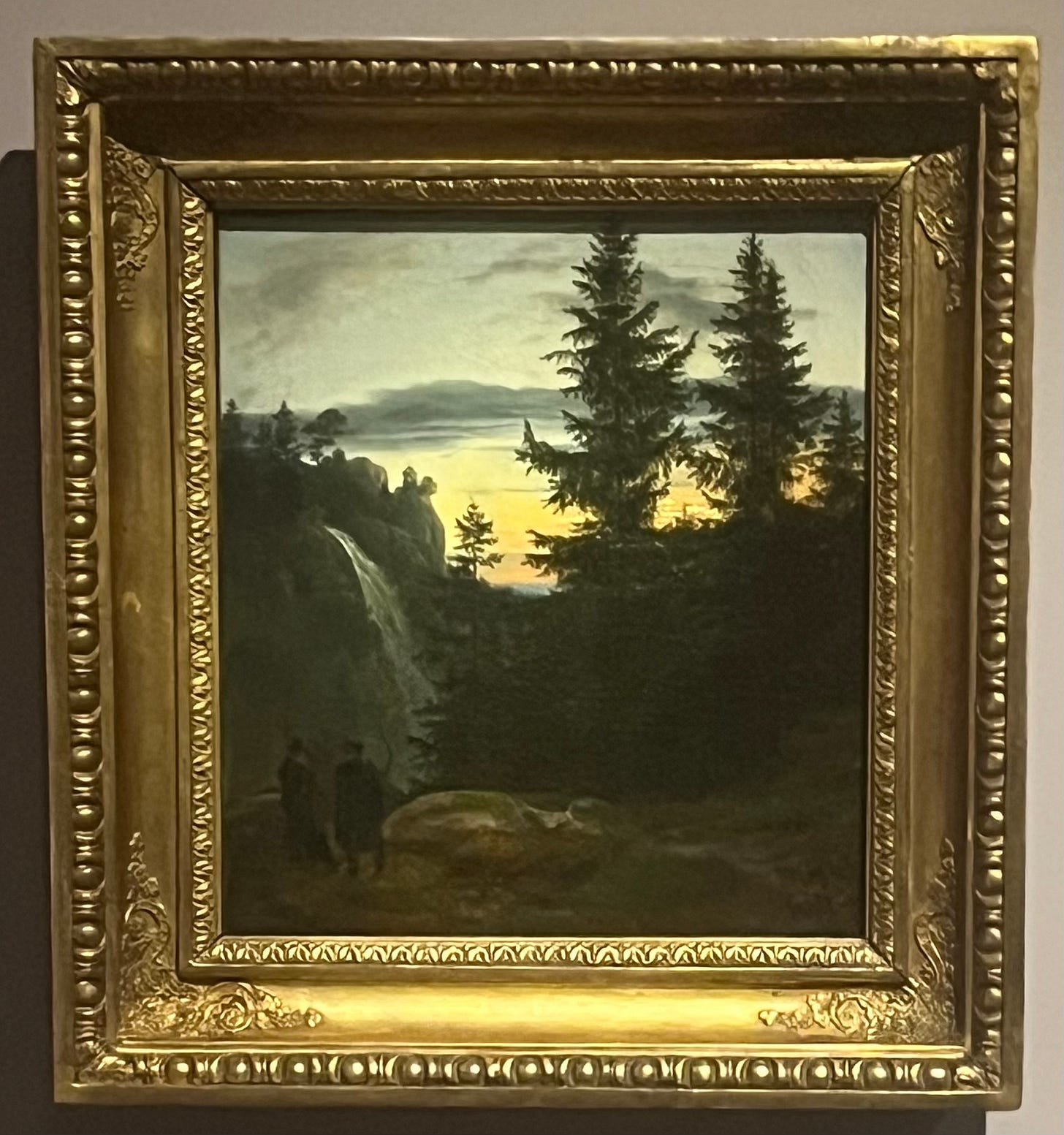

I came up from DC to visit the MET this weekend, because I wanted to see the Caspar David Friedrich exhibition before it closed (1774–1840). Happily, the trip was well worth it, and Caspar did not disappoint.

He was a magician with light, and the show was pure joy, although some of the paintings had a melancholy feel to them, particularly those which he made towards the end of his life.

His most well known canvass is “Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog,” which is often on lists of the most famous Western paintings, but I thought that a number of his other works were more impressive.

Great as Caspar is, however, he was not the highlight of my visit.

One of the joys of big, encyclopedic art museums is that you often discover stuff through chance that you quickly fall in love with. Today, I didn’t plan to see the Jesse Krimes exhibition, and I had no clue who he was before I walked in, but now he’s one of my favorite artists.

Krimes studied art in college, but later got into serious trouble, and spent six years behind bars for a drug related offense - the wall text didn’t provide further details about the nature of his crime. Whether he learned his lesson on the criminal side, I have no idea, but he certainly used the time productively from a creative standpoint. Here’s the museum summary of his work:

Krimes’s image-based installations, made over the course of his six-year incarceration, reflect the ingenuity of an artist working without access to traditional materials. Employing prison-issued soap, hair gel, playing cards, and newspaper he created works of art that seek to disrupt and recontextualize the circulation of photographs in the media. Displayed at The Met in dialogue with Bertillon, whose pioneering method paired anthropomorphic measurements with photographs to produce the present-day mug shot, Krimes’s work raises questions about the perceived neutrality of our systems of identification and the hierarchies of social imbalance they create and reinscribe. An artist for whom collaboration and activism are vital, Krimes founded the Center for Art and Advocacy to highlight the talent and creative potential among individuals who have experienced incarceration and to support and improve outcomes for formerly incarcerated artists.

To be sure, an incarcerated felon urging people to be more empathetic toward prisoners is hardly a novel phenomenon. And while I have nothing against this mission per se, I have experienced being completely knocked out by two violent men on a sidewalk in Adams Morgan (a DC neighborhood), so I am not the kind of progressive liberal who is against prisons and policing. Reform - absolutely; defunding - no.

Put simply, I take Krimes’ message about empathy seriously not because he was a criminal who was punished by the state, but because he’s an outstanding artist.

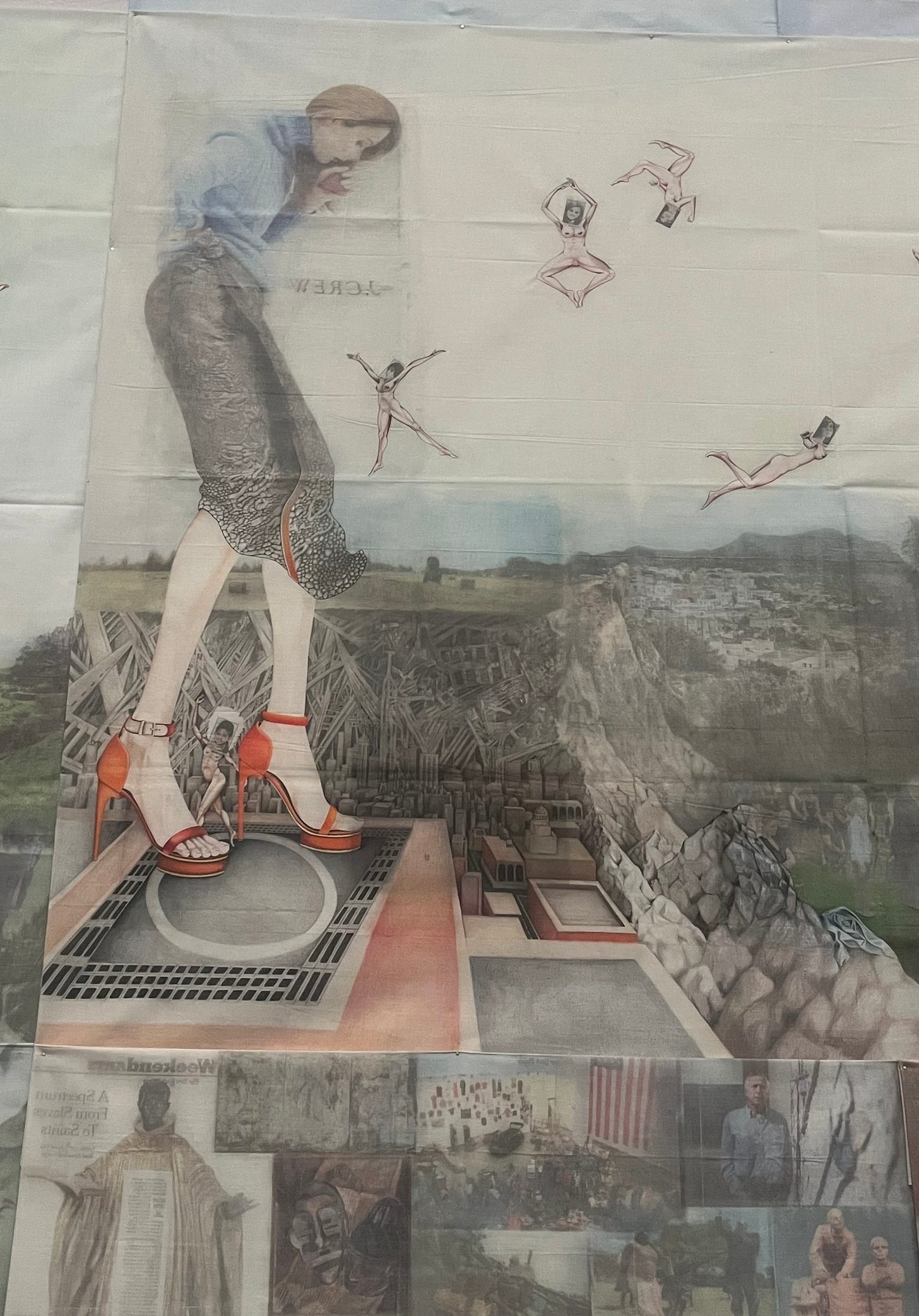

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a wall length mural based on images from the New York Times. It’s called Apokaluptein: 16389067. Here’s the wall text, kindly converted into cut-and-pastable text by Claude:

Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982) Apokaluptein: 16389067 (2010–13).

Cotton sheets, ink, hair gel, graphite, gouache.

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

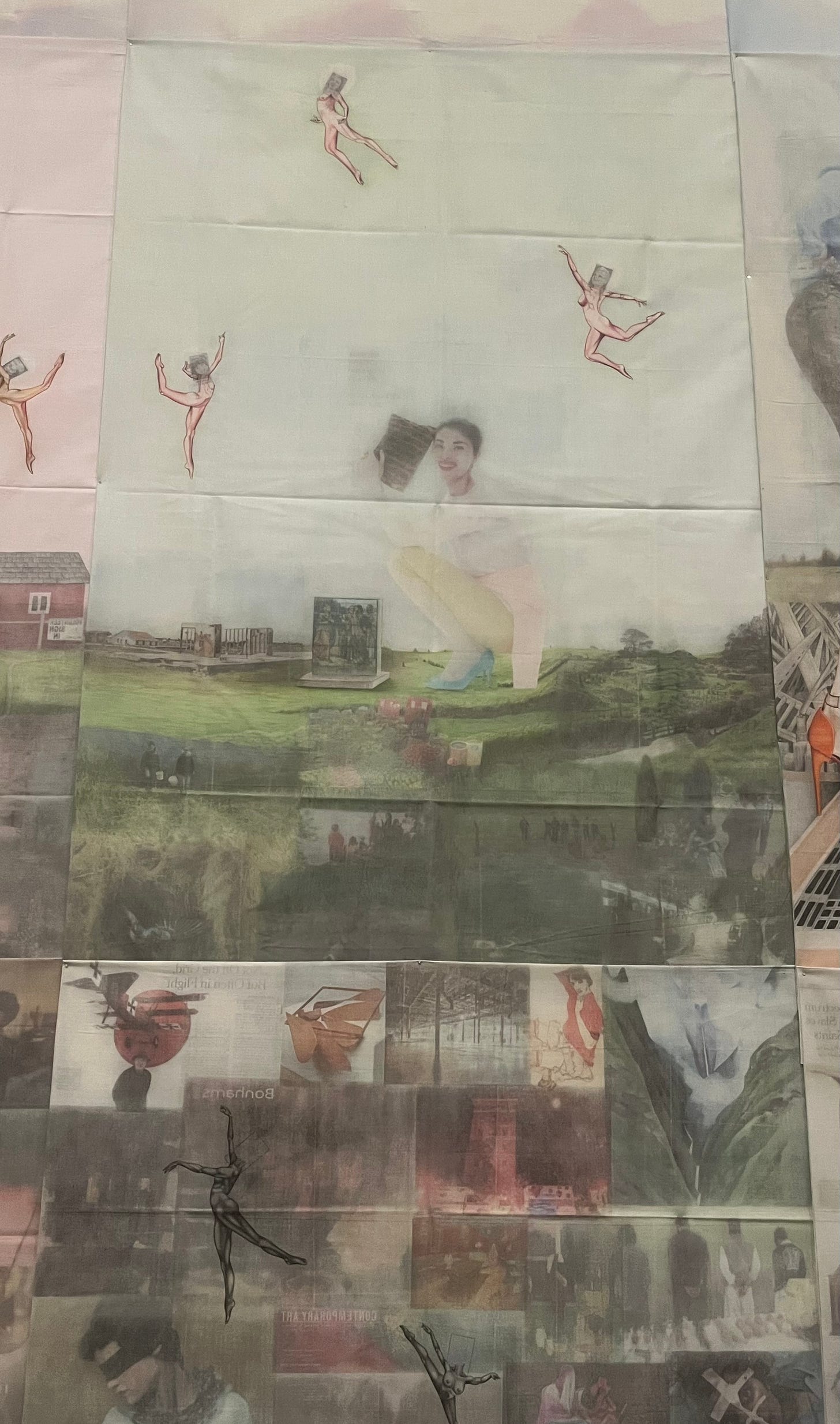

Krimes's magnum opus presents a surreal landscape—heaven, earth, and hell—through a collage of source images published in the New York Times between 2010 and 2013. He composed the work on thirty-nine prison-issued bedsheets, adding hand-drawn alterations, and sent them out of prison one section at a time. The title pairs a Greek word (the origin of apocalypse) that means "to uncover" or "to reveal" with the artist's prison identification number. With a limited lens on the outside world, Krimes relied on newspapers; he began to notice a misalignment between journalistic narratives and the symbolism in accompanying photographs. By reconfiguring pictures and their related stories into a three-part landscape of reward and punishment, Krimes suggests how images can be used to control and influence populations. The new visual narratives invite us to experience the world—inverted by image transfer—through the artist's incarcerated perspective.

And here’s the work itself, followed by some photos of particular sections that stood out to me.

I spent at least twenty minutes looking at the mural, and it’s the kind of piece that I wish I could revisit at my leisure. It looks great whether one views it as a whole, or breaks it down into its component parts, and the Campbell’s soup can towering over a landscape is plain genius.

The images speak for themselves - or don’t, depending on your taste - so I won’t belabor the point. Rather, I’ll conclude by noting that while Krimes calls for empathy toward prisoners, his artwork didn’t really affect my views on that subject. Instead, while immersing myself in the exhibition, I thought about empathy toward maga. Notably, if liberals think that empathy toward prisoners is appropriate, despite their crimes, then perhaps they should be more empathetic toward fascist republicans, despite their deeply toxic views on a wide range of vital issues.

Selective empathy can be better than no empathy at all; but, logically, empathy only makes sense if it is applied universally. However, regardless of how desirable universal empathy may be as a general concept, it is strikingly difficult to implement in practice. For example, here’s a Berkshire Eagle article about a recent ICE raid in Great Barrington.

I suppose I could empathize with these absurdly heavily armed thugs if I put my mind to it, but I really don’t want to.